Loop Haiti

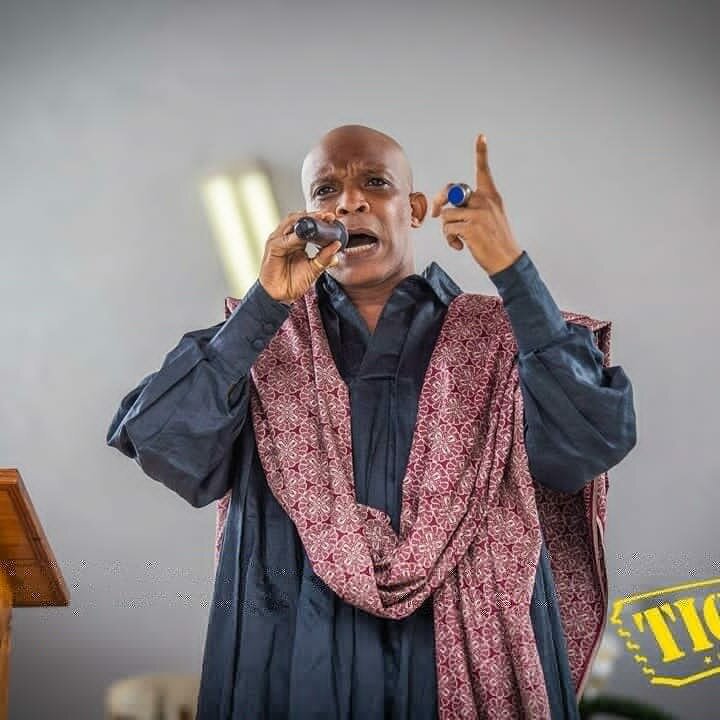

Erol Josué, singer-songwriter, dancer, houngan, and author of the album “Pèlerinaj”, electrified the Caribbean Cultural Center (CCC), on October 29, 2023, with his performance on the Studio Fest Show stage which was the scene of a spectacular event. The event, which took place as a prelude to the Day of the Dead or the “Gede” period in Haiti (November 1 and 2), was a memorable moment that ignited the Studio Fest show, which every Sunday welcomes Haitian musical talents, whether established or still unknown to the general public. Accompanied by his troupe, the performer of “Gason solid” chained together songs from his discography, notably from his latest album as well as from the voodoo register, and this, with an overflowing energy. Apparently in a trance on several occasions, his powerful voice transcended the room, carrying the audience away in a whirlwind of emotions. Traditional Haitian rhythms mixed with modern melodies to create a captivating musical experience, transforming the CCC into a true sanctuary of music where the stage presence of the multi-talented artist dominates. Related Article Culture 7 Things You Don’t Know About Guédés November 1, 2018 01:19 PM ET The dancers, who accompanied the singer during his feat, brought a unique dimension to the concert. These talented dancers moved on stage with grace and energy, giving more life to Erol’s voice. Their movements, inspired by the “Gede” period, traditional Haitian dances and tinged with voodoo symbolism, created a bewitching atmosphere. Their presence on stage not only enhanced the visual aspect of the show, but also contributed to the musical narrative, adding an extra layer of authenticity. The audience at the Caribbean Cultural Center was composed mainly of young people, especially students, who came from all over the region to attend this magical event. The musicians were dressed in black, embellished with purple, as was the group of dancers who accompanied the artist at times to create an enchanting atmosphere that recalled the “Gede” spirits. The Gede, as explained by the expert on Haitian voodoo culture and history, is “a space of debauchery, a mirror of society where we parody the “masters” of the colonial era, an opportunity to celebrate life and celebrate our dead.” Advertisement Beyond his hellish performance, what made this event even more memorable was the interaction between the artist and the audience through the show’s host. Between each session, he answered questions from Marc Anderson Bregard, sharing anecdotes about his musical journey, his commitment to Haitian culture, his love for voodoo tradition, and the connection between the construction of the canal [on the Massacre River, editor’s note] and cultural practices. “The construction of the canal is a pilgrimage on the path of our right, of our sovereignty as a people,” said the one who believes that life is a pilgrimage. Asked about the various voodoo ceremonies organized for the advancement of the construction of the canal, the houngan had to say: “I think it is important, it is what we call substantivity. Haiti has never done anything without voodoo. […] Voodoo was the cornerstone of the Haitian revolution.” This canal, continued the educator, is the straw that must break the camel’s back and give us back our sovereignty which comes through food self-sufficiency. 0 seconds of 2 minutes, 47 seconds Volume 90% The audience, visibly won over, reacted with enthusiasm, showing their admiration for the artist. Actively participating in this “show never done at the CCC”, as Bregard said, the fans chanted with rhythm and boldness “Abinader, se kanal n ap fouye, se pa charite n ap mande” [Abinader, we are digging an irrigation canal, we are not begging. Editor’s note]. This cry, a parody of the song “Pèlerinaj” by Erol Josué, symbolized the determination of the Haitian people to preserve their sovereignty in the face of the Dominican head of state, Luis Abinader, who is trying to establish his supremacy over the entire island, particularly during the resumption of construction of the canal drawing on the Massacre River initiated in 2018 and resumed on August 30, 2023 by peasants from Ferrier. The composer left an indelible mark on the hearts of his audience. The spectators, carried by the passion and authenticity of the artist, expressed their gratitude by dancing and singing with him until the last notes of music. Erol Josué’s performance at the Caribbean Cultural Center was much more than a simple concert. It was a celebration of Haitian culture, voodoo tradition, and the artistic talent of the director of the National Bureau of Ethnology (BNE). Erol Josué’s album “Pelerinaj” was voted the best album in the history of Haitian music in the “Top of the World CD” by Songlines magazine. The prestigious British magazine Songlines has just released its December issue. On the cover of the latest issue of this magazine distributed in some sixty countries, we can see the Haitian ethnologist and singer Erol Josué, in an originally African and Caribbean couture. For good reason, his album Pelerinaj has just been ranked the best album in the history of music in Haiti, in the magazine’s “Top of the World CD”. https://www.facebook.com/plugins/post.php?href=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2FOfficialErolJosue%2Fposts%2Fpfbid02xupjsMjxXQxa2tv4GcdjLz2niKoqHG54WrDH5Fk3ANA2kqkcqSp6N6qKFejiEVsWl&show_text=true&width=500 Songlines, a magazine launched in 1999 that covers traditional and popular, contemporary and fusion music, features artists from around the world. In its list of the best albums in different musical styles and different countries in the world for this year, it is Erol Josué who wins the place of the best album in the history of music in Haiti and one of the best albums in the world music industry, with his album Pelerinaj released on May 28, 2021. “Album Erol Josué klase kom pi bèl album nan listwa mizik en AYITI epi kom youn nan pi bèl album nan endistri world music la” , we can read on the Facebook page of the current director of the National Bureau of Ethnology. https://www.facebook.com/plugins/post.php?href=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2FOfficialErolJosue%2Fposts%2Fpfbid0K771PR5A9rxYpf4nKiXA6jMX8VFqdjhRsVaNBzsGYPwJrX9fwxcKruj8bWprx6kAl&show_text=true&width=500 Advertisement In the announcement made by Songlines on its official website, the magazine highlights the work that the Haitian ethnologist and singer is doing to change the bad ideas conveyed throughout the

The World

Erol Josué is a dancer, a recording artist, a vodou priest, and an expert on the vodou religion’s culture and history. “They beat me in the name of Jesus,” Josué sings in one song. “They burn me in the name of Jesus.” The lyrics of this old vodou song date back to slavery days in the 18th Century, but their warning rings true today for some vodou practitioners — or vodouisants — who feel under attack. The old joke goes that Haiti is 70 percent Catholic, 30 percent Protestant and 100 percent Vodou. For Josué, this is no joking matter. Last year, he took a government job as head of Haiti’s National Ethnology Office. He’s on a mission to get Haitians to realize that they need to embrace their vodou heritage — whether they agree or not. Ground zero for the tension is Bwa Kayiman, a site in northern Haiti. A late-night meeting there in 1791 set in motion what would become one of history’s most successful slave revolts. It’s essentially where the country of “Haiti” was born — as a union of different tribes, faiths and languages. “It was the moment the slaves said, ‘We’ve become Creoles today; we’re no longer African. We won’t fight to return to Africa, but for this land,’” Josué said. These days, Bwa Kayiman is a mess. On a visit with a team of ethnologists, Josué found a handful of historical sites unmarked and decaying. This is supposed to a heritage site, but buildings have been built illegally, including Protestant churches. Josué is not happy. “Vodou has never been a religion of conquest,” he says. “We don’t raise awareness to convert people to vodou, but to educate them about the importance of the national identity, the importance of respecting the sites, of respecting the patrimony. The churches and houses that were built on the Bwa Kayiman site is, personally, a kind of sacrilege. But it’s also an attack on the state.” This “attack,” as Josué puts it, comes mainly from the evangelical movement. Unofficial estimates suggest about half of Haitians are Protestant these days, a rise fueled in large part by American-funded evangelical missions, churches and schools. Elizabeth McAlister is a Haiti scholar at Wesleyan University, and a long-time friend of Josué’s. “The evangelical movement desires to reduce vodou entirely, if they could they would have a Christian revival and transform the country to a Christian majority,” she says. McAlister says there’s no question that foreign religious influence is affecting Haitians’ attitudes about vodou, but she says that even many Haitians feel the vodou religion and culture is something they would rather leave in the past. “Among educated and other people who see vodou as always having been denigrated, always having been insulted, the discourse on vodou are either that it’s an illegal practice or it’s a practice of superstition done by the ignorant,” she says. “Meanwhile, so much of the culture is infused with the principles of the form. So it creates a tension, psychologically — how does one represent the culture, and how does one come to terms with being from this culture which is so saturated with this religion?” Vodou’s influence is felt just about everywhere in Haiti, from the country’s music and art to the latest locally-designed fashions and accessories on display in uptown boutiques. As head of the Haitian ethnology office, Josué has demonstrated and lobbied to create the first national holiday to honor vodou. Like it or not, he says, vodou is soaked deep into Haiti’s local and international brand — as an aesthetic, a philosophy and a way of life. “You can be what you want, but stay a Haitian. Stay a proud Haitian,” Josué says. Ferreira’s reporting was supported by a grant from the International Reporting Project.

Le Nouvelliste

At Fokal, this past Friday, June 24th, was the climax, the final celebration with fireworks. The festival culminated with a beautiful show. The flyers featured two major individuals, true glories of Haitian music: scholarly composer and violinist Daniel Bernard Roumain, accompanied by pianist Yayoï Ikawa; and ethnologist, Vodou priest, dancer, singer, and actor emeritus Erol Josué Emeritus, supported by his group Nègès Fla vodou and the tambours d’Haïti. A Guitarist and pianist were his guests. Daniel Bernard Roumain, a Haitian American, was born in Skokie, Illinois in 1970. He has been playing the violin since the age of 5 and holds a doctorate in composition from the University of Michigan. He is a postmodern creator interested in African-American popular music, the distorted sounds of “rock” and cyber. He does not love less the music of Haiti, the country of origin of his parents. He sees himself as a Haitian. He approached this encounter from a scholarly, elaborated and familiar angle. Playing the electric violin and viola, not Si vous avez déjà créé un compte, connectez-vous pour lire la suite de cet article. Connectez-vous Pas encore de compte ? Inscrivez-vous Lire aussi

Pop Matters

Erol Josué is a vodou priest. This is far from being a secret. Every article about him mentions it, and Régléman‘s press kit revolves around it. “At age 17, Josué was initiated as a houngan, or vodou priest. Josué’s mother is a vodou priestess and his late father … was a vodou priest.” After a while this vodou priest vodou priest vodou priest business starts to feel like a prompt. A little man in a box in the wings is poking us with a long cane. He hisses. “Psst! You know what we’re talking about — that album. The vodou priest one! By that man! The vodou priest man!” As it turns out this is actually a help. There’s a gravity to Régléman that becomes immediately deepened and explicable when you realise that the Haitian singer is being religious. This kind of information does change things. The Hallelujah Chorus wouldn’t sound the same if you thought that hallelujah was a brand of canned peas. Or: it would sound the same, but you’d understand it differently. And vodou (or voodoo, or however you’d like to spell it) is a religion that could do with some widespread rehabilitating. Witness: Voodoo Devil Drums. (1944) “She was doomed to die! See — for the first time — the virgin dance of death! The altar of skulls! The walking death! Strange secrets never before revealed!” Voodoo Tiger (1952): “Voodoo Vengeance Runs Riot!” Curse of the Voodoo (1964): “Jungle Terror! Native Fury! Blood sacrifice of the Simbai!” Voodoo Heartbeat (1975): “SERUM OF SATAN – One drop … and a raging monster is unleashed to kill … and kill again in an unending lust for blood!” Voodoo (1995): “Life is Full of Sacrifices.” Voodoo Lagoon (2006): “Paradise can be Hell.” (Witness also: the voodoo story in Dr Terror’s House of Horrors, voodoo used as an excuse for mad scientist-type antics and zombies wearing face cereal in I Eat Your Skin (which was titled Voodoo Blood Bath until they decided to put it on a double bill with I Drink Your Blood, a movie about killer hippies), and Bela Lugosi using his magic powers to keep kidnapped women in a state of suspended animation under his house in Voodoo Man.) The music on Régléman is so beautiful and the presentation so hip and nonchalantly pretty that it makes the zombie-slave blood-of-satan notions of vodou look even more cartoonish than they already do. The CD case contains the dedication to God that, totem-like, accompanies so many U.S. albums on their journey into the world, but this time the god is “Olorum, master of the universe, creator of the four elements.” After that, Josué thanks his fellow musicians, his mum, his brothers and sisters, his granny, his dad, his stepdad, his niece Emeraude Esperanta who “brought sunshine into our lives.” It’s all very normal, and a million miles away from the altar of skulls, the virgin dance of death, and raging monsters unleashed to kill and kill again in an unending lust for blood. It may not make you like the album any more or any less, but it’s interesting to know that Josué has his hand over one eye on the album cover because he does this before he begins a ceremony (“I always touch my eyes to go down into my soul to be open and ready for my spirit”), and that the album opens with singing and percussion because vodou ceremonies do, too (“a conversation between Hounto, the spirit of the drum, and Legba, the god of wisdom, who opens the gates for all the spirits to enter the ceremony”). Musically, the album takes many of its cues from Afropop. There are traces of Angélique Kidjo in here, and doses of Boukman Eksperyans, a Haitian roots-rock success story that released its first album in 1991. Josué, like Boukman and other racine musicians, makes a point of emphasising Haiti’s connections to Africa, particularly Benin, the source of vodou — and the source of Kidjo as well, although I think any similarities between him and her have more to do with her status as an African-born pop artist with international reach than they do the country she was born to. As a musician from a quasi-African culture trying to get a message across, it’s natural that he should look to someone else who has had triumphs of her own in roughly the same area. It seems strange to me that I like this album, because a lot of the Afropop that appears in the world music section — the kind that seem predestined for the world music section, as this does — often seems tame or dated, the result of a musician trying to please too many people at once, or the work of someone who has never realised that there is more to western music than the blandest songs on the radio. Afro-freakfolk, where art thou? The word alone — “Afropop” — makes me growl and shudder. As soon as I hear it I think that I’m up for an encounter with Blandie McBland. Yet Régléman is undeniably part of that undistinguished family. And I do not hate it. Why? Well, for one, Josué, who currently lives in New York, has had his antennae out and he’s been listening to music other than the top 40. . The percussion in that opening song, “Hounto Legba”, includes a scuzzily metallic thumb-piano that is the living spit of Konono No. 1. Electronic noises swell darkly in “Yege Dahomen” as if the song has been remixed by Lamb. A multi-tracked chanting old woman on “Balize” folds herself into samba lounge-jazz with Josué’s voice moving in twists over the top, while a faint psychedelic tingle in the background of “Madam Letan” suggests that magical mystery tours are about to start. The song spins along at a merry-go-round bob. All of this has the effect of making the album seem mutable and borderline weird: it’s neither strange nor conventional but some odd, exciting hybrid. Régléman sounds similar to a lot of other things without fundamentally being like them. There’s something about his singing, too, a measured passion, an elegance that gives the album an unfaltering flow. It redeems

The Loop

« Pelerinaj » le dernier album d’Erol Josué, sorti le 28 mai 2021, vient d’être classé en 7ème position des plus beaux albums au monde dans le Word Music Chart Europe. En début de semaine, le chanteur, danseur, prêtre vodou, anthropologue et professeur d’université, Erol Josué a partagé sur Facebook une nouvelle faisant honneur à son art d’une part mais d’autre part, à tout le peuple haïtien. Son dernier album, « Pelerinaj » sorti le 28 mai 2021, occupe la septième 7ème parmi les plus beaux albums au monde dans le Word Music Chart Europe 2022. L’actuel directeur du Bureau National d’Ethnologie a invité le public à célébrer cette nouvelle qui, selon lui, permettra, entre autres, de démystifier le vodou aux yeux du monde. On peut lire sur sa page Facebook : « Bat bravo pou li » ou encore « Atis la rantre ak vodou a nan tout salon ». Contacté par Loop, le chanteur en a profité pour nous parler de son album, mais aussi de ce que ce classement signifie pour lui et pour la culture haïtienne. Mais d’abord l’album. Josué nous confie que l’œuvre en question est un parcours de vie. « C’est plus qu’un album de musique, c’est l’histoire, une bande sonore qui raconte l’histoire contemporaine de façon contemporaine », a-t-il dit, ajoutant que son disque traite de sujets haïtiens. C’est aussi, souligne-t-il, un collectage de sons et de textes qui viennent du vodou haïtien. « J’ai travaillé avec des musiciens contemporains de divers horizons dans le monde, mais à la base c’est vodou, je parle de société, d’environnement et du droit à la différence », nous a-t-il fait savoir. Advertisement En ce qui concerne ce classement et ce qu’il signifie pour lui, le chanteur s’en dit heureux et surtout fier. « Ce classement signifie beaucoup pour moi. Lorsqu’on fait de la musique et qu’on reçoit de telle reconnaissance, ça t’aide encore, ça te donne l’énergie pour pouvoir continuer. » Josué nous confie au passage qu’il a passé 10 ans à travailler sur cet album dont la sortie a été bloquée par le « Peyi lòk » ainsi que la Covid19. Maintenant qu’il est sorti, l’opus semble bien parti pour laisser sa trace. L’anthropologue se réjouit de continuer à promouvoir le vodou au-delà des frontières haïtiennes. Il croit que cette distinction signifie que le monde écoute ce que Ayiti a à dire et à offrir: « Comme on dit en Créole ‘’ Nou rive sou yo ’’ ».

Songlines: ( Best Album – Haiti)

Erol Josué knows how to call down and speak to the lwa (spirits) that visit the ceremonies he conducts in Haiti and with Haitians around the world. A houngan (vodou priest) since his teens, he speaks langaj, a liturgical vocabulary of words once spoken in Benin and Congo and by Haiti’s Indigenous Taíno. The lwa, flattered by langaj, are channelled through trance: Erzulie, the goddess of love and beauty; Chango, the blacksmith with the purifying fire; and the psychopomp Papa Gede, the dancing spirit of life and death, the lwa with the galaxy in his hips. “Langaj is the secret language of vodou,” says Josué, a 21st-century renaissance man who is a singer, songwriter, dancer, actor, lecturer and director general of the National Bureau of Ethnology in Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s capital. “It cannot be translated except through rituals and dreams. But as practitioners, we feel it. We use langaj in songs, dances [and] incantations to calm or to change a mood.” An African diasporic religion with roots in Benin (formerly Dahomey), vodou (also spelled voodoo) is part of the fabric of Haiti, that spectacular, beleaguered nation sharing the island of Hispaniola with the Dominican Republic. Langaj was formerly spoken by maroons, the escaped slaves who fled into remote mountains and formed communities that – during and after the Haitian Revolution of 1791-1804 – were crucial in the fight to abolish slavery, overturn colonialism and establish the world’s first Black republic. Erol Josué (photo: Verdy Verna) “I learned langaj as a child from my parents and grandparents, all of them houngans and manbos [vodou priestesses],” continues Josué, Zooming from a hotel room in Port-au-Prince. He’s had to temporarily leave his home due to the recent violent anti-government protests in September, which spilled over into attacks on property and citizens including, notably, vodou practitioners – who are frequently blamed for the crises that beset Haiti. Josué sprinkles langaj across the 18 tracks that make up his second album, Pelerinaj: “I’m presenting a way of life using sacred and secular language,” he says. “Even though these songs were composed for musicians to play, not for use in rituals, they present spiritual knowledge.” A homage to vodou’s abiding principles of community, tolerance and sharing, to its affinity with ecology, life cycles and ancestral wisdom, Pelerinaj (‘Pilgrimage’ in Haitian Creole) comes some 15 years after its predecessor, Regleman (Mi5 Recordings), a debut album that mirrored the vodou ceremonies that Josué was then conducting inside New York’s Haitian community. Pelerinaj blends sacred chants and traditional rhythms (dogo, noki, fla voudon) with elements of funk, jazz, rock and electronic music. He sings mostly in Haitian Creole as well as French. The album is an ambitious, even epic, work with a reach that spans a lifetime, from Josué’s childhood home in Kafou, a sprawling outer suburb of Port-au-Prince, through his journey out of Haiti and two decades spent living between Paris, New York and Miami to his eventual return, to his Caribbean birthplace, first as a traveller undertaking a series of timeworn vodou pilgrimages, then as a proud repatriate. “The songs on this album were recorded over several years with a range of musicians and producers. But the tracks build on each other so that it feels like one large work,” says Josué, whose dramatic golden tenor conjures centuries of history on album opener, ‘Badji’, a song featuring the vast choir of the National Theatre of Haiti alongside archive samples from the court of the king of Ouidah in Benin (where vodoun is an official state religion). The lyrics tell of the secret transmission of knowledge from the Indigenous Taíno to Africans transported to Haiti. “The Taíno used the word badji to mean ‘high mountains.’ I use it to refer to the high spirituality of this country. It is our duty to protect the transmission of the legacy, the badji of Haiti.” Erol Josué (photo: Verdy Verna) The Bureau National d’Ethnologie, which Josué has helmed since 2012, strives to do just that. Founded in 1941 by Haitian writer Jacques Roumain and located on Champ de Mars, a noisy crossroads in Port-au-Prince, its remit is to preserve and champion Haitian culture (housing, for example, a huge cache of stolen Taíno artefacts recently returned from the US by the FBI). The culture of vodou is a priority. For despite a peaceable aesthetic that include the notion of lakou – broadly, a family-oriented compound with a communal worship area and a peristil (shrine) around a sacred mapou tree – the religion is couched in negative misconceptions. Superstition and Hollywood sensationalism carry much of the blame. As does the dictatorial Duvalier dynasty, which exploited vodou practitioners to bolster their rule (1957-1986). As does evangelical Christianity. “Most people who practice vodou in Haiti live in the countryside,” explains Josué. “The Catholic church is always trying to convert them. Children are beaten at school if they do not speak French well. I was able to maintain my vodou spiritual life at home while attending Catholic school during the day. I never converted. Now I help to dispel the myths.” He also reminds Haitians – and listeners – of the nation’s heritage. ‘Je Suis Grand Nèg’ (I Am a Great Man/Negro) is re-modelled from a traditional paean to the resilience of Haiti. ‘Kwi a’, with its rousing percussion and chorus by the all-female Nègès Fla Vodoun choir (“my bodyguards in Port-au-Prince”), says that as descendants of freedom fighters, as sons and daughters of Africa, Haitians should not use the kwi, a hollowed calabash, to beg. On ‘Sigbo Lisa’, a Creole-sung, langaj-dotted song acknowledging the power of West Africa’s griot oral tradition, Josué vows never to betray his lwa, his ancestors, or his Haitian culture. Erol Josué (photo: Verdy Verna) Still, in the early 2000s, returning to Haiti wasn’t on Josué’s mind. He had a new passport and a new family of friends. A graduate of Haiti’s National School of Arts, he’d become a key cultural figure in Europe and New York after variously establishing his own dance troupe in Paris, performing alongside Afro-Brazilian artists on the 2004 album Orixás by Jorge Amorim & Hank – a work celebrating Candomblé, a syncretic religion that, like Cuban Santería,